CLOSER THAN YOU THOUGHT? PARALLELS, PROJECTIONS, REFLECTIONS

The former mining town of Bottrop is the "smallest major city" of the 53 neighbouring towns along the Ruhr and Emscher rivers. Here, over 5 million inhabitants not only experience and shape one of the largest conurbations in Europe and the largest in Germany, but also a psychopolitical "coincidence of opposites". On the one hand, at the site of the smoking chimneys of the German "Wirtschaftswunder" (economic miracle), that began in the 1950s, there was a successful, "top-down" organised prevention of concentrated metropolitan power in the hands of the traditionally strong labour movement in the mining and industrial region. The words of the first German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer "When the Ruhr is on fire, even the water of the Rhine is not enough to put it out" are as well-known as they are paradigmatic in this respect. On the other hand, there were – not only in football – traditional city rivalries within the Ruhr region. Even more formative, however, was the solidary, heterogeneous and decentralised neighbourhood culture in the colliery settlements and districts, which continues to this day in countless informal networks with a pronounced immunity "bottom up": against any centralised administrative power.

A colourful, heterogeneous and sometimes paradoxical urban structure. It also has a truly unique distinguishing feature: an externally imposed division of administrative power into three separate districts. This means that the Ruhr region is still not administered from a separate, industrially and multi-ethnically characterised unit. The three administrative centres of the Ruhr are located outside the actual conurbation: in Münster in Westphalia, in Düsseldorf in the Rhineland and in Arnsberg in the Sauerland. There is no doubt that the "Ruhr region" differs from these three cities in terms of landscape, culture, economy, social structure and mentality to a far greater extent than the same three regional centres do from one another.

As a historically young and rapidly growing coal and steel region, the Ruhr area is characterised by the cultural diversity of its population. This is reflected in all areas of life - but especially in art and culture. In addition to a wide range of museums, opera houses, cinemas, theatres and music theatres, the region has established itself over the last three and a half decades as a centre of attraction for urban planners, monument conservationists, architects, performance, sound and light artists, designers, photographers and, last but not least, filmmakers under the key term of "industrial culture".

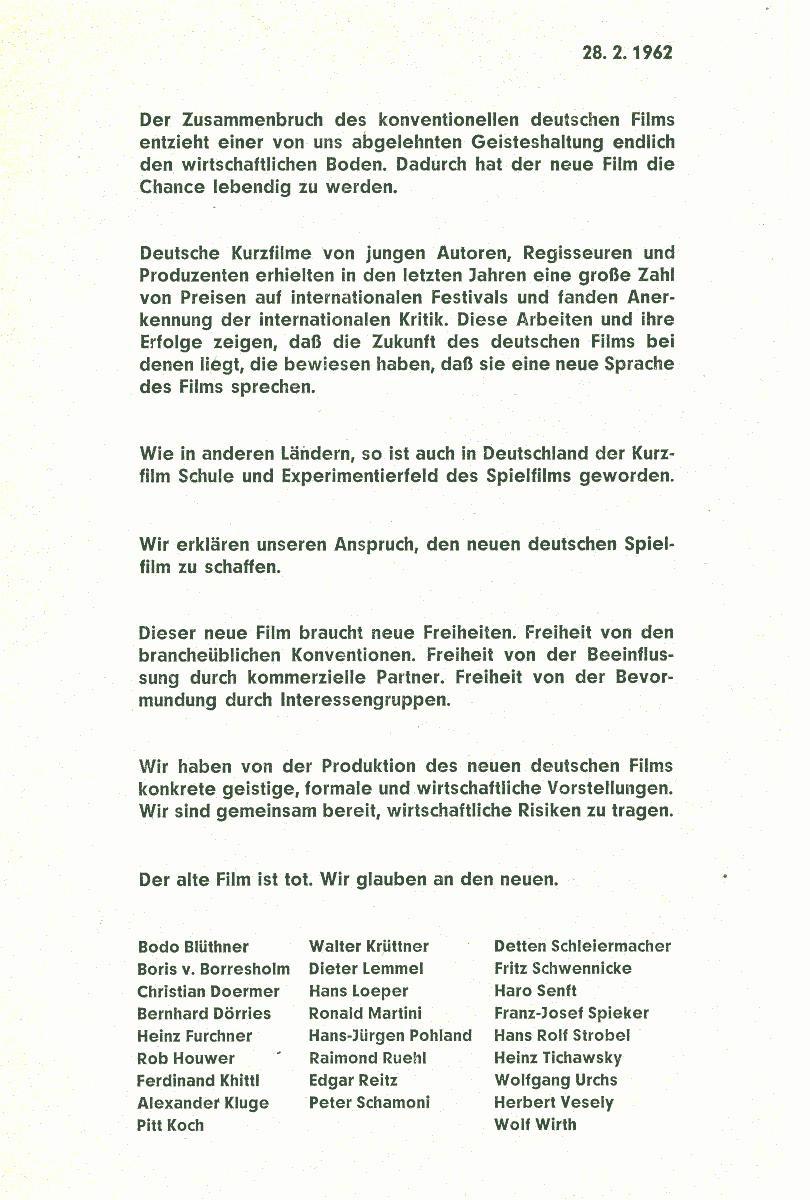

As far as the medium film is concerned, no one in the Ruhr region can ignore a historic date. On 28 February 1962 – just a handful of kilometres away from Bottrop – German film history was written with the proclamation of the Oberhausen Manifesto by 26 filmmakers against massive resistance. The framework was provided by the 8th edition of the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, founded in 1954 and thus the oldest short film festival in the world. The manifesto presented at the time by the young Alexander Kluge aimed at nothing less than a radical and comprehensive reorganisation of filmmaking in Germany. The first stone was set rolling here for many structures in the film industry that are still decisive and fundamental today – including the public film funding, film schools and the success of the New German Cinema as a specific variety of the international tradition of auteur film.

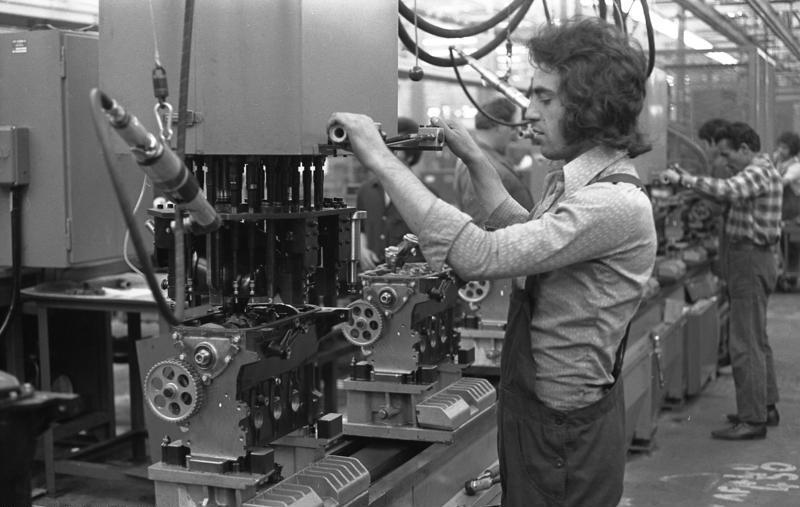

Almost exactly at the time of the Oberhausen Manifesto, the city of Bottrop – like the entire Ruhr region after the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 and the end of the immigration of labour from the GDR – became a place of work, refuge and hope for good fortune for many people from southern Europe. After the first labour recruitment agreements with Italy in 1954, Spain and Greece in 1960 and Turkey in 1961, Portugal, Morocco, Tunisia - and Yugoslavia in 1968 - followed by the end of the 1960s.

These agreements not only reduced unemployment figures in the countries of origin. The foreign currency that flowed back from the workers in Germany to their home countries also became an important factor for the local economy.

Many of the migrants, who had originally only come as "guest workers" for a temporary labour assignment and were almost exclusively male, soon took the opportunity to bring their families to join them. For the first time, Bottrop and the Ruhr region became the trigger for many breaks in Bosnian lives: as a place of hope for happy new beginnings. Or at least a place of longing for it. For many, however, it was also a place of disillusionment. Even in those years, the culture of welcome proved to be dependent on productivity and the cyclic economic development. The advantage of the recruitment agreement with Yugoslavia only lasted from 1968 to 1973. The oil crisis of 73/74 ended the first dream of Germany and Europe for many families. It was not to be the last.